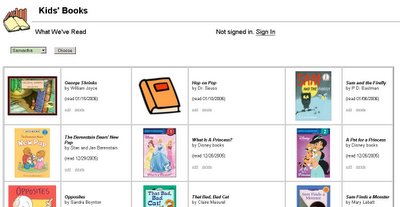

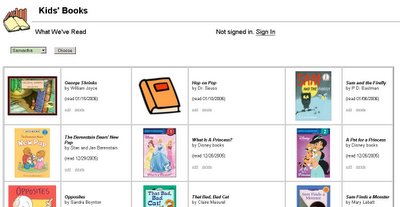

The children's booklist is working a little more smoothly than it was a week ago. Check it out to see what some of our children have been reading lately.

My own reading (Tolstoy's Resurrection) will get pushed aside today while I browse the Fifth Carnival of Homeschooling.

Teaching strategies and family humor from inexperienced-but-trying, homeschooling parents.

January 31, 2006

January 30, 2006

Why My Son Reads

Recently I caught Nathaniel reading to his little sister, Jessica. Getting Nathaniel to read is always a challenge, so you can imagine the warm thrill that went through me when I overheard them.

That morning he had read The Berenstain Bears and the Spooky Old Tree to me. He had enjoyed the story, but once we closed the book, I thought it was over.

That afternoon the kids were being suspiciously quiet, so I went to check on them, half expecting to uncover activity that would necessitate a trip to Home Depot. I heard Nathaniel's voice through the slightly-open door, and something in his tone made me linger a moment.

He was reading! To his sister! Without parental compulsion!

I flung open the door with pride. "So, you're reading to your sister, Nathaniel!"

Both children looked at me impatiently, even aloof.

"Dad, we're trying to read. Leave us alone."

These glimpses of looming adolescence scare me in my young children. I left them.

A week or two went by, and I realized that Nathaniel wasn't reading to Jessica anymore. I asked why not.

"I don't read to Jessica," he said flatly.

"But you had fun reading her The Spooky Old Tree, didn't you?"

"Oh, that," he said as if I should have been able to figure this out on my own. "That was to scare her."

That morning he had read The Berenstain Bears and the Spooky Old Tree to me. He had enjoyed the story, but once we closed the book, I thought it was over.

That afternoon the kids were being suspiciously quiet, so I went to check on them, half expecting to uncover activity that would necessitate a trip to Home Depot. I heard Nathaniel's voice through the slightly-open door, and something in his tone made me linger a moment.

He was reading! To his sister! Without parental compulsion!

I flung open the door with pride. "So, you're reading to your sister, Nathaniel!"

Both children looked at me impatiently, even aloof.

"Dad, we're trying to read. Leave us alone."

These glimpses of looming adolescence scare me in my young children. I left them.

A week or two went by, and I realized that Nathaniel wasn't reading to Jessica anymore. I asked why not.

"I don't read to Jessica," he said flatly.

"But you had fun reading her The Spooky Old Tree, didn't you?"

"Oh, that," he said as if I should have been able to figure this out on my own. "That was to scare her."

January 25, 2006

Homeschool Paperwork Reduction Act

HB 406

Last week the state legislature approved House Bill 406, the "Homeschool Paperwork Reduction Act." The result is that New Hampshire homeschoolers no longer need to file curriculum plans with the school districts at the start of each school year. Now we need only administer annual achievement tests to confirm our children's progress.

Common sense favors the passage of this bill:

On the other hand, the requirement to submit a curriculum, while bureaucratic and unnecessary, wasn't really harmful:

Can Red Tape Protect Homeschoolers?

I wonder if the curriculum requirement actually protected homeschoolers. We're a minority, but by keeping one toe in the public educational system, we show our willingness to participate in majority culture. Submitting a curriculum helps to keep the uneasy alliance between public educators and homeschoolers from becoming a rift.

Here's the worst thing that I can imagine happening to the homeschool movement:

A parent who is abusive or negligent or otherwise criminal chooses to homeschool his children—but not in order to educate them. He does it in order to fly under the radar. He doesn't want his kids in school because teachers might notice the scars or hear that Daddy makes bombs in the basement. (We store books in our basement, but I do have a vivid imagination!)

Might this insignificant, cursory, bureaucratic requirement pose a barrier to such a person?

I don't know.

But if such a horror story ever does make the New Hampshire nightly news, I bet there will be somebody pointing out that the children of homeschoolers are totally outside of the system, that homeschoolers don't even have to share a curriculum with the state. Then where will we be?

Last week the state legislature approved House Bill 406, the "Homeschool Paperwork Reduction Act." The result is that New Hampshire homeschoolers no longer need to file curriculum plans with the school districts at the start of each school year. Now we need only administer annual achievement tests to confirm our children's progress.

Common sense favors the passage of this bill:

- The requirement to submit a curriculum was redundant, since annual evaluations ensure that homeschooled children are receiving an adequate education.

- There was no standard form for describing a curriculum. How could the government judge whether one parent's three-sentence write-up described a better or worse education than another parent's table of contents from a purchased curriculum?

- The requirement created extra paperwork for homeschoolers and the school districts alike.

- It just doesn't make sense for public school districts to review homeschool curricula. How could a public school district, committed to the separation of church and state and the mainstreaming of special-needs children, go about approving, for example, the distinctly Christian curriculum of a homeschooler who withdrew her children from public school because she didn't believe the school was addressing their special needs?

- In practice, curricula were collected, but never reviewed. (I don't know this for sure—it's what I understand from anecdotal evidence.)

On the other hand, the requirement to submit a curriculum, while bureaucratic and unnecessary, wasn't really harmful:

- Submitting a curriculum wasn't onerous. We struggled with how to begin because there were so few samples online, but Camille assembled our curriculum in a few hours.

- I'm not convinced it hurts to lay out a year-long plan for your child's education, even if you end up changing it.

- Reviewing New Hampshire's public educational requirements in order to submit a curriculum gave us confidence that we weren't overlooking anything in our own plans.

- Having our curriculum "approved" (even though it was probably never reviewed), was psychologically reassuring. It felt less like we were sneaking around the system. It validated our choice to homeschool.

Can Red Tape Protect Homeschoolers?

I wonder if the curriculum requirement actually protected homeschoolers. We're a minority, but by keeping one toe in the public educational system, we show our willingness to participate in majority culture. Submitting a curriculum helps to keep the uneasy alliance between public educators and homeschoolers from becoming a rift.

Here's the worst thing that I can imagine happening to the homeschool movement:

A parent who is abusive or negligent or otherwise criminal chooses to homeschool his children—but not in order to educate them. He does it in order to fly under the radar. He doesn't want his kids in school because teachers might notice the scars or hear that Daddy makes bombs in the basement. (We store books in our basement, but I do have a vivid imagination!)

Might this insignificant, cursory, bureaucratic requirement pose a barrier to such a person?

I don't know.

But if such a horror story ever does make the New Hampshire nightly news, I bet there will be somebody pointing out that the children of homeschoolers are totally outside of the system, that homeschoolers don't even have to share a curriculum with the state. Then where will we be?

January 23, 2006

Kids' Books -- Online Reading List

A while back I was thinking that I wanted the kids to have a place online where they could track what books they had read.

I wanted:

If you want to see what Nathaniel and Jessica have been reading lately, check out www.Books.CriticalMap.com. Click on "Darth Vader" (Nathaniel) or "Samantha" (Jessica) in the list, and then click the Choose button.

If you like this system, you are welcome to try adding your own child's reading. The instructions are below.

(Please keep in mind that this site is a hobby for me, not a job . . . and that you get wait you pay for!)

How to Add Your Child's Reading to the List in Just 8 (formerly 14!) Steps

Your child's books won't show up with pictures at first. As time permits, Camille and I will fill in the graphics.

Let me know what you think!

I wanted:

- A site anybody could visit to see what the kids have been reading lately.

- A forum where the kids could post very short “reviews” to recommend books to friends.

- Anonymity for children online.

If you want to see what Nathaniel and Jessica have been reading lately, check out www.Books.CriticalMap.com. Click on "Darth Vader" (Nathaniel) or "Samantha" (Jessica) in the list, and then click the Choose button.

If you like this system, you are welcome to try adding your own child's reading. The instructions are below.

(Please keep in mind that this site is a hobby for me, not a job . . . and that you get wait you pay for!)

How to Add Your Child's Reading to the List in Just 8 (formerly 14!) Steps

- Go to www.Books.CriticalMap.com.

- Click on Sign In.

- Click on the words Click to Register.

- Fill out a name, a password, and an email address. (I will absolutely never share the email with anyone under any circumstances. I'll use it only to confirm passwords or notify you of any changes.)

- Click Your Settings.

- Click Add a Child to Your List.

- Enter the name you want to appear for the child and click the button. (I'm not comfortable putting our kids' names on the Internet, so I let the kids pick their own "Code Names.")

- You should see a link next to the Choose button called Add a Book. Click it, and you can start building your child's reading list.

Your child's books won't show up with pictures at first. As time permits, Camille and I will fill in the graphics.

Let me know what you think!

January 17, 2006

Homeschooling Blogs and E.B. White

Lately I've been reading One Man's Meat by E.B. White. I've decided this book is a blog from a time before blogs.

I admire E.B. White. He's the sophisticated writer from The New Yorker who led an alternate life on a small farm on the coast of Maine. He's the terse wordsmith who gave us the latter half of Strunk and White's The Elements of Style. He's the children's author who invented Charlotte's Web and The Trumpet of the Swan: books that should be staples of any child's reading.

One Man's Meat is a collection of essays written after he moved to his farm in 1938. The essays aren't quite articles, and they aren't quite diary entries either.

He tells of his first efforts to keep hens and how he dealt with a surplus of eggs. He compares his dog to one in an advertisement for Camel cigarettes. He sings the praises of his son's one-room schoolhouse—the boy had previously attended an elite private school in New York. He tells of shingling his barn while Britain and France gave Czechoslovakia to Hitler via the Munich Accord.

For more contemporary blogs related to homeschooling, see the Cate family's Carnival of Homeschooling, Week 3.

I admire E.B. White. He's the sophisticated writer from The New Yorker who led an alternate life on a small farm on the coast of Maine. He's the terse wordsmith who gave us the latter half of Strunk and White's The Elements of Style. He's the children's author who invented Charlotte's Web and The Trumpet of the Swan: books that should be staples of any child's reading.

One Man's Meat is a collection of essays written after he moved to his farm in 1938. The essays aren't quite articles, and they aren't quite diary entries either.

He tells of his first efforts to keep hens and how he dealt with a surplus of eggs. He compares his dog to one in an advertisement for Camel cigarettes. He sings the praises of his son's one-room schoolhouse—the boy had previously attended an elite private school in New York. He tells of shingling his barn while Britain and France gave Czechoslovakia to Hitler via the Munich Accord.

For more contemporary blogs related to homeschooling, see the Cate family's Carnival of Homeschooling, Week 3.

January 15, 2006

Skating and Raising the Bar

Last week we took the kids skating for the first time at a pond in beautiful, nearby White Park. (Actually the pond was a lot more beautiful before some zealot from the DOT decided that the playing fields needed to be snowplowed in order to provide parking for the skaters, but that's another story.)

Last week we took the kids skating for the first time at a pond in beautiful, nearby White Park. (Actually the pond was a lot more beautiful before some zealot from the DOT decided that the playing fields needed to be snowplowed in order to provide parking for the skaters, but that's another story.)Nathaniel was a natural on ice. Jessica cried the first time she felt unsteady on her legs, immediately fell down and threw a tantrum, and spent most of the outing on her belly. Seeing her took me back to my own childhood when my brother and I went skating. Neither of us was a natural, like Nathaniel. I just sulked and refused to skate. My brother followed Jessica's example, crying and sitting on the ice.

My parents were sympathetic and protective, and I never did learn to skate--not well, anyway. I wonder if they did us a disservice?

My wondering points to a fundamental question of teaching: to what extent should we pamper our children and ease their learning, and to what extent should we push our children and urge them beyond their capabilities?

Public schools fail to raise the bar for most kids just because they teach to a point that sits slightly left of average on the bell curve. (I'm sure some would dispute this claim, but I'm convinced of it from my own teaching and schooling. Anecdotal evidence from other public school teachers confirms my opinion.) A teacher with 27 students who are struggling to subtract isn't able to spend much time encouraging the 3 who are almost able to divide.

Homeschool teachers can more easily raise the bar. We can more easily lower it, too. If Johnny is an “actual-spontaneous” learner (an energetic, hands-on type who dislikes bookwork), Mom faces a real temptation. After all, she could customize Johnny's education so much toward his strengths and away from his weaknesses that Johnny never will learn self-discipline, or read for pleasure, or be able to wait for something worthwhile. On the other hand, in an effort to overcome any weaknesses in Johnny's personality, Dad might push too hard, until Johnny despairs and believes himself a failure.

I conclude that this question of raising the bar is a balancing act. We have to watch our kids, weigh their triumphs and failures, and decide when and how hard to push.

. . .

Or so I thought.

The end of this story belies my reasoning. Camille took the kids skating again the following day. Nathaniel, aggressive and cocky on his second day out, fell hard and broke his clavicle: he's out for the season. Just before skating was aborted for a trip to the hospital, however, Jessica, under pressure, on her own time, perhaps feeling a competitive urge to match her brother's performance, started skating. She has been out for a third time, and she's really taking off.

So Nathaniel, whom we didn't push at all, tried so hard that he literally broke himself. And Jessica, whom I worried that I was pushing too hard, is flourishing. If this means something, I don't know what it is.

January 10, 2006

Kids and their Interests

We homeschoolers talk a lot about our students' “self-directed” or “self-led” or “interest-guided” education. The idea is that students should be able to pursue their own interests. After all, if a particular child loves construction, why not gear her science lessons around the physics of a tower crane and her history lessons around pyramid-building?

Certainly my own experience tells me this is a good idea. I distinctly remember wanting to learn more about things that my public schooling touched on: world religions, electric motors, the Wright brothers. Each time I had to abandon those interests because the class “needed to move on.”

I want to be careful about this self-directed learning, however, because—in my own experience—the opposite was also true.

I never wanted to study math, although I've always had a gift for it. If I hadn't been forced to study trigonometry, I never would have enjoyed a career in 3D computer graphics. If I hadn't been forced to read Dickens, I would have missed out on novels that have played a part in forming my character.

The classes I now wish I had taken in college—music history, chemistry, a classical language—are the very ones I willfully avoided. Some of the electives that I pursued instead were “lighter” classes, and probably a waste of my time.

What we want to learn, especially when we are young, is not necessarily what we ought to learn. If Plato was right that cave-dwellers need to be dragged out into the light, then perhaps we shouldn't be so quick to let our children choose the tunnels they think lead to the surface.

In fact I think that homeschooling is less self-directed than we homeschoolers let on. It's a rare child whose interests include learning phonics or memorizing multiplication tables, but homeschooled kids are almost invariably more facile readers and multipliers than their institutionally schooled counterparts.

If we really let that construction-minded daughter determine her own education, she might well choose to remain illiterate among the Tonka trucks in her sandbox. By letting her choose books about construction, we're meeting her halfway. We're balancing an appeal to her current interests with what we believe she needs to know.

Certainly my own experience tells me this is a good idea. I distinctly remember wanting to learn more about things that my public schooling touched on: world religions, electric motors, the Wright brothers. Each time I had to abandon those interests because the class “needed to move on.”

I want to be careful about this self-directed learning, however, because—in my own experience—the opposite was also true.

I never wanted to study math, although I've always had a gift for it. If I hadn't been forced to study trigonometry, I never would have enjoyed a career in 3D computer graphics. If I hadn't been forced to read Dickens, I would have missed out on novels that have played a part in forming my character.

The classes I now wish I had taken in college—music history, chemistry, a classical language—are the very ones I willfully avoided. Some of the electives that I pursued instead were “lighter” classes, and probably a waste of my time.

What we want to learn, especially when we are young, is not necessarily what we ought to learn. If Plato was right that cave-dwellers need to be dragged out into the light, then perhaps we shouldn't be so quick to let our children choose the tunnels they think lead to the surface.

In fact I think that homeschooling is less self-directed than we homeschoolers let on. It's a rare child whose interests include learning phonics or memorizing multiplication tables, but homeschooled kids are almost invariably more facile readers and multipliers than their institutionally schooled counterparts.

If we really let that construction-minded daughter determine her own education, she might well choose to remain illiterate among the Tonka trucks in her sandbox. By letting her choose books about construction, we're meeting her halfway. We're balancing an appeal to her current interests with what we believe she needs to know.

January 07, 2006

Cave Paintings

Today the kids made cave paintings.

Camille had read them a book about the paintings discovered in 1994 in Chauvet-pont-d'arc, France. (Add this to the list of places we have neither time nor money to visit!)

The book generated enough excitement that the side of our stairs now displays early woolly mammoth realism on butcher paper. They even used primitive ink and brushes: blueberry juice spread via sticks hammered flat so that their fibers splay. For logistical reasons, they skipped the primitive scaffolding.

The book also mentioned that scientists are unable to identify the subjects of some cave art. Camille showed the kids one of these cryptic paintings and asked if they had any hypotheses. After scrutinizing the photo, Nathaniel said, “Well, they don't look as good as the other ones. I bet the cave kids painted those.”

In our ignorance of art pre-history, this strikes Camille and me as a pretty good theory. If we were busily trying to decorate the cave, we might well send the kids to the other end and let them paint their own chunk of the wall.

Camille had read them a book about the paintings discovered in 1994 in Chauvet-pont-d'arc, France. (Add this to the list of places we have neither time nor money to visit!)

The book generated enough excitement that the side of our stairs now displays early woolly mammoth realism on butcher paper. They even used primitive ink and brushes: blueberry juice spread via sticks hammered flat so that their fibers splay. For logistical reasons, they skipped the primitive scaffolding.

The book also mentioned that scientists are unable to identify the subjects of some cave art. Camille showed the kids one of these cryptic paintings and asked if they had any hypotheses. After scrutinizing the photo, Nathaniel said, “Well, they don't look as good as the other ones. I bet the cave kids painted those.”

In our ignorance of art pre-history, this strikes Camille and me as a pretty good theory. If we were busily trying to decorate the cave, we might well send the kids to the other end and let them paint their own chunk of the wall.

January 05, 2006

Kids and Sleeping

I've heard that children "look innocent when they sleep."

Not in my house, they don't.

Nathaniel, six, sleeps hard, his body retaining whatever contorted pose it was in when it hit the mattress. If you pull up his blanket, he frowns, in his sleep, at being disturbed. He winces when he hears the door open, and he rolls over and grunts in disgust if the light comes on. His bed is his own, and he wants his slumber respected.

He sweats fiercely, regardless of the room's temperature. Putting him to bed, I can't shake the feeling that I've just inserted a battery into its charger: crackling and hot, his little dozing shape is already working up fresh havoc for sunrise.

My five-year old, Jessica, rests serenely, but not sweetly. She sleeps with her tongue out, always. This results in a constant trickle of drool.

Once when we changed the sheets, Jessica, who was about three, crawled into her bed and grew agitated right away. "Where's my Scratchy?" she asked. My wife and I failed to understand, and since three-year olds don't excel at clarification, she just repeated, with increasing vehemence, "Where's my Scratchy?—-I need it to sleep with."

This was a mystery. Jessica sleeps with a rag that was once a doll, suitably named "Dolly." Nathaniel sleeps with his stuffed animals: "Lamby" the lamb and "Herder" the sheepdog. (We don't put a lot of work into naming our plush toys.) But Scratchy was a new member of the menagerie. Our parenthood had reached one of those moments that should really stay where they belong—-in horror movies.

Who was the enigmatic "Scratchy"? Could it be a reference to "Old Scratch"? You don't like to think your family requires an exorcist, but strange ideas cross your mind when your toddler is frantic over being unable to go to bed with someone you don't know.

After a half hour of hypotheses disproved by experimentation (We: "Did you say 'flashlight'?" She, bawling: "No!!!") we learned that her "Scratchy" referred to the part of her sheet where her head always rested. There the cotton actually got stiff from repeated nightly applications of drool, so it scratched her face. Without our knowing, she had given it a name.

Now Jessica delights in having her sheets washed. "Tonight I'm going to make a new Scratchy," she says on laundry day, with precisely the sort of pride, determination, and relish with which she does not say, "Now I'm going to make a letter 'G.'"

I said that Nathaniel sleeps in whatever awkward position he happened to be in when he hit the sheets. This is not an exaggeration. We've peeked at him in the middle of the night to find his butt in the air and his knees bent, all his weight on his chest. We've found him lying sideways across the bed, on his back, with his head hanging upside down over the side. We've found him with one leg in his pajamas, zombie-like, asleep and standing with only his head resting on the bed.

It used to be worse. I once went to check on him and couldn't open the door. My first instinct was to push hard against whatever was blocking it. This wasn't wise as the obstruction turned out to be my son's head. Why he had crawled out of bed and fallen asleep against the door we've never known.

I've known parents who have taken their children on drives just to help them fall asleep. Something about the ambient sound and the gentle vibration of an automobile has a soporific effect on babies.

Not on ours. When my son was still taking two naps per day, we decided to undertake the drive from New Hampshire to Chicago in sixteen hours, stopping only for gas and fast food. Nathaniel was alert, vociferous, and cranky for all sixteen.

Once my wife and I slept with the kids. We're not one of those progressive couples who do this for developmental reasons—-it was just a special treat. A one-time treat, as it turns out. I learned that Nathaniel occasionally yells in his sleep. My wife reports that Jessica pinches.

This morning my son inexplicably popped out of his charger before 5:00 am. We watched Arthur together, and when Nathaniel got on the floor beside me, I put my head on his belly and teased, "Just what I need, a nice warm pillow." Naturally, he started giggling and wriggling, and I tried to pin him to the floor while my wife shook her head with that mixture of pride and disgust she feels when she sees that I relate better to seven-year olds than adults.

Jessica decided to rescue her brother. She jumped onto my back (knees first), saying "Now I have a nice warm pillow—and it's Daddy!"

Before I could get away she added, "And I can make a Scratchy on you."

Not in my house, they don't.

Nathaniel, six, sleeps hard, his body retaining whatever contorted pose it was in when it hit the mattress. If you pull up his blanket, he frowns, in his sleep, at being disturbed. He winces when he hears the door open, and he rolls over and grunts in disgust if the light comes on. His bed is his own, and he wants his slumber respected.

He sweats fiercely, regardless of the room's temperature. Putting him to bed, I can't shake the feeling that I've just inserted a battery into its charger: crackling and hot, his little dozing shape is already working up fresh havoc for sunrise.

My five-year old, Jessica, rests serenely, but not sweetly. She sleeps with her tongue out, always. This results in a constant trickle of drool.

Once when we changed the sheets, Jessica, who was about three, crawled into her bed and grew agitated right away. "Where's my Scratchy?" she asked. My wife and I failed to understand, and since three-year olds don't excel at clarification, she just repeated, with increasing vehemence, "Where's my Scratchy?—-I need it to sleep with."

This was a mystery. Jessica sleeps with a rag that was once a doll, suitably named "Dolly." Nathaniel sleeps with his stuffed animals: "Lamby" the lamb and "Herder" the sheepdog. (We don't put a lot of work into naming our plush toys.) But Scratchy was a new member of the menagerie. Our parenthood had reached one of those moments that should really stay where they belong—-in horror movies.

Who was the enigmatic "Scratchy"? Could it be a reference to "Old Scratch"? You don't like to think your family requires an exorcist, but strange ideas cross your mind when your toddler is frantic over being unable to go to bed with someone you don't know.

After a half hour of hypotheses disproved by experimentation (We: "Did you say 'flashlight'?" She, bawling: "No!!!") we learned that her "Scratchy" referred to the part of her sheet where her head always rested. There the cotton actually got stiff from repeated nightly applications of drool, so it scratched her face. Without our knowing, she had given it a name.

Now Jessica delights in having her sheets washed. "Tonight I'm going to make a new Scratchy," she says on laundry day, with precisely the sort of pride, determination, and relish with which she does not say, "Now I'm going to make a letter 'G.'"

I said that Nathaniel sleeps in whatever awkward position he happened to be in when he hit the sheets. This is not an exaggeration. We've peeked at him in the middle of the night to find his butt in the air and his knees bent, all his weight on his chest. We've found him lying sideways across the bed, on his back, with his head hanging upside down over the side. We've found him with one leg in his pajamas, zombie-like, asleep and standing with only his head resting on the bed.

It used to be worse. I once went to check on him and couldn't open the door. My first instinct was to push hard against whatever was blocking it. This wasn't wise as the obstruction turned out to be my son's head. Why he had crawled out of bed and fallen asleep against the door we've never known.

I've known parents who have taken their children on drives just to help them fall asleep. Something about the ambient sound and the gentle vibration of an automobile has a soporific effect on babies.

Not on ours. When my son was still taking two naps per day, we decided to undertake the drive from New Hampshire to Chicago in sixteen hours, stopping only for gas and fast food. Nathaniel was alert, vociferous, and cranky for all sixteen.

Once my wife and I slept with the kids. We're not one of those progressive couples who do this for developmental reasons—-it was just a special treat. A one-time treat, as it turns out. I learned that Nathaniel occasionally yells in his sleep. My wife reports that Jessica pinches.

This morning my son inexplicably popped out of his charger before 5:00 am. We watched Arthur together, and when Nathaniel got on the floor beside me, I put my head on his belly and teased, "Just what I need, a nice warm pillow." Naturally, he started giggling and wriggling, and I tried to pin him to the floor while my wife shook her head with that mixture of pride and disgust she feels when she sees that I relate better to seven-year olds than adults.

Jessica decided to rescue her brother. She jumped onto my back (knees first), saying "Now I have a nice warm pillow—and it's Daddy!"

Before I could get away she added, "And I can make a Scratchy on you."

January 04, 2006

Comparing Two Readers

I marvel at how differently our two kids read.

Nathaniel, seven, sounds out almost every word. Even words that he has read over a hundred times now, he likes to sound out first. This habit gets him into trouble with words that don't fit phonics patterns: this morning they were “sure” and “want,” although he appears at last to have mastered “thought” and “could.”

On the other hand, he approaches new words fearlessly.

Once he “gets” a word after sounding it out, he feels no need to repeat it clearly, but just plods right on to the next word. If Mom or I ask him to repeat it, he will say it adroitly without sounding it out again, proving that he really did understand what he read. (He's not happy if we interrupt him this way.) I'm always surprised that he has no problem comprehending a whole sentence on the first pass, even if he spent some 30 seconds struggling with three or four different words in it.

Jessica, five, memorizes words quickly. If an “I Can Read” book presents the same word several times, she will have mastered it after its first or second appearance. Thereafter she reads it at a glance. If she bumps into the word again two days later, she usually recalls it easily.

She's quicker than Nathaniel to give up on a new word, turning to Mom or me for help.

Jessica likes her reading to sound clean. After she finally works out a difficult word, she'll back up and repeat it with the correct intonation.

On the whole, she seems to be picking up reading faster than Nathaniel did. I don't know how much of this difference is due to differences in the children and how much of it is due to the fact that Nathaniel was in public kindergarten last year. Much of Jessica's kindergarten homeschooling involves participating in Nathaniel's first-grade lessons, so she's being exposed to more, earlier. Our curriculum emphasizes reading more than the public school's did, so she's just getting more practice, too.

Nathaniel, seven, sounds out almost every word. Even words that he has read over a hundred times now, he likes to sound out first. This habit gets him into trouble with words that don't fit phonics patterns: this morning they were “sure” and “want,” although he appears at last to have mastered “thought” and “could.”

On the other hand, he approaches new words fearlessly.

Once he “gets” a word after sounding it out, he feels no need to repeat it clearly, but just plods right on to the next word. If Mom or I ask him to repeat it, he will say it adroitly without sounding it out again, proving that he really did understand what he read. (He's not happy if we interrupt him this way.) I'm always surprised that he has no problem comprehending a whole sentence on the first pass, even if he spent some 30 seconds struggling with three or four different words in it.

Jessica, five, memorizes words quickly. If an “I Can Read” book presents the same word several times, she will have mastered it after its first or second appearance. Thereafter she reads it at a glance. If she bumps into the word again two days later, she usually recalls it easily.

She's quicker than Nathaniel to give up on a new word, turning to Mom or me for help.

Jessica likes her reading to sound clean. After she finally works out a difficult word, she'll back up and repeat it with the correct intonation.

On the whole, she seems to be picking up reading faster than Nathaniel did. I don't know how much of this difference is due to differences in the children and how much of it is due to the fact that Nathaniel was in public kindergarten last year. Much of Jessica's kindergarten homeschooling involves participating in Nathaniel's first-grade lessons, so she's being exposed to more, earlier. Our curriculum emphasizes reading more than the public school's did, so she's just getting more practice, too.

January 03, 2006

Why Homeschool: The Carnival of Homeschooling: week 1

For lots of other homeschoolers' blogs, see Why Homeschool: The Carnival of Homeschooling: week 1. It offers a nice cross-section of the homeschooling community.

January 01, 2006

All By Himself

Nathaniel read a book alone for the first time yesterday.

Well, not a whole book. He read two stories out of Arnold Lobel's Frog and Toad Together.

Like too many of our homeschooling triumphs, this was the result of a dispute.

Nathaniel loves stories: making them up, hearing them, and acting them out. He doesn't love reading. We speculate that in his mind it comes down to a question of efficiency: why should he struggle through a book, slowly, when he knows Mom or Dad could read it to him effortlessly?

Some other time I might address the various strategies we've used to coax, prod, and compel Nathaniel to read. Now we require him to read a book to us almost every day. If he refuses, we tell him to stay in his room, with the book, until he is ready to read.

Yesterday he refused. After twenty minutes alone in his room, he approached me.

“Are you ready to read now?” I asked.

“I already read it,” he said, trying to suppress a smile of pride.

I'm ashamed to admit I was skeptical. I quizzed him thoroughly while paging through the story myself, and he not only comprehended it beyond what the pictures revealed, but he was quoting some of the characters' lines.

It was a good day for literacy, in spite of its unpromising start!

(By the way, the Frog and Toad series of short stories is an excellent place for beginning readers to spend some time. The books do a neat job of reinforcing vocabulary by repeating phrases in the course of simple, natural dialog. The illustrations eventually won my son's heart as well, although he was initially put off by the earth-tone coloring.)

Well, not a whole book. He read two stories out of Arnold Lobel's Frog and Toad Together.

Like too many of our homeschooling triumphs, this was the result of a dispute.

Nathaniel loves stories: making them up, hearing them, and acting them out. He doesn't love reading. We speculate that in his mind it comes down to a question of efficiency: why should he struggle through a book, slowly, when he knows Mom or Dad could read it to him effortlessly?

Some other time I might address the various strategies we've used to coax, prod, and compel Nathaniel to read. Now we require him to read a book to us almost every day. If he refuses, we tell him to stay in his room, with the book, until he is ready to read.

Yesterday he refused. After twenty minutes alone in his room, he approached me.

“Are you ready to read now?” I asked.

“I already read it,” he said, trying to suppress a smile of pride.

I'm ashamed to admit I was skeptical. I quizzed him thoroughly while paging through the story myself, and he not only comprehended it beyond what the pictures revealed, but he was quoting some of the characters' lines.

It was a good day for literacy, in spite of its unpromising start!

(By the way, the Frog and Toad series of short stories is an excellent place for beginning readers to spend some time. The books do a neat job of reinforcing vocabulary by repeating phrases in the course of simple, natural dialog. The illustrations eventually won my son's heart as well, although he was initially put off by the earth-tone coloring.)

Teacher's Dream or Teacher's Nightmare?

Homeschooling is a teacher's nightmare. . . .

- The pay is even worse than usual.

- Regardless of their specializations, faculty are required to teach every subject, every day.

- Every year requires a new prep. Faculty are prohibited from teaching the same grade twice.

- Faculty are expected to provide the entire budget—for equipment, resources, help from specialists, extracurriculars, everything—out of their own personal finances.

- The students see the faculty as parents first and teachers second: there is no “professional distance.”

- There are no free periods; no solitude during lunch or recess.

- Opportunities for professional development are underfunded.

- Instructors cannot count on NEA support. Sometimes the NEA actively opposes them.

- September doesn't bring a new crop of students. Teachers don't get to start fresh or meet new faces.

- The retirement plan stinks. So does the medical. And the insurance.

- Little peer support is available. Faculty don't share lunch in the lounge.

- Instructors don't ever teach the same topic twice. They have no opportunity to rework or improve a lesson during the next class or the following school year.

- There is no janitorial staff. Teachers are responsible for cleaning their rooms.

- The institution doesn't offer any on-the-job training or refresher courses. Keeping up with the latest educational thinking is left to the faculty.

- The school day never ends.

Homeschooling is a teacher's dream. . . .

- The class sizes are small.

- All parents are fully committed to their children's education.

- Instructors control their own curricula.

- Classrooms have windows. The thermostats work.

- None of the students come from dysfunctional homes.

- Ample opportunities exist to bond with students outside of the classroom setting.

- No union membership is required.

- There are no faculty meetings.

- Teachers can hug the students without being charged with sexual harassment.

- The institution is always open to new ideas, methods, and subjects.

- Students don't disappear into the void every June, never to be heard from again.

- The work environment is warm, inviting, and free of cockroaches. There is adequate faculty parking.

- Coordinating cross-disciplinary lessons is a breeze. (The history teacher, for example, is always willing to offer lessons on the Civil War while the English teacher is working on The Red Badge of Courage.)

- Instructors don't have to “teach to the test.”

- Parents invariably support faculty decisions.

- Faculty can choose their own textbooks and instructional materials.

- No overpaid consultants sell the school on “systems,” “methodologies,” or other easy answers.

- Teachers do not hear from lawyers if they give unsatisfactory grades or discuss religious beliefs in the classroom.

- The schedule is flexible.

- The cafeteria is excellent, though self-serve.

- The administration doesn't dictate an instructor's pedagogical methods.

- Teachers see the long-term fruits of their work.

- The school doesn't even have a mission statement, but education is, truly, its number one concern.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)